Or more precisely, is it oscillating, or is it not oscillating?

This is my first attempt at actually trying to build a circuit using Manhattan style construction (so please, be kind!) I fetched the oscillator circuit from EMRFD, and tacked it together with some parts from my junkbox. The only substitution that I made was that the two 390pf capacitors were replaced with 220pf capacitors. My understanding (limited as it might be) is that this is parallel capacitance for the crystal, and should move the oscillating frequency somewhat closer to the frequency of the crystal (in this case, 7.040 Mhz) than the specified design.

Here are some photos:

EMRFD says that this should oscillate at very low voltage levels, so I powered it up with a 9 volt battery. No magic smoke was released, but fishing around the design frequency using my FT-817ND, I heard nary a trace of it anywhere near the design frequency. If I had an oscilloscope, it would probably be pretty easy to tell, but I don’t (hey, I told you I was new at this). I fished around with my multimeter a bit, measuring continuity and the like. The overall resistance between the positive voltage supply and ground is about 19k ohms, indicating an overall current draw of about 0.4ma (with the 9 volt supply). That seems low, but maybe not excessively low. Measuring the base voltage on the transistor, I get about 3.35 volts. Again, that seems reasonable to me.

For all I know, it could be oscillating, but at a low power level. I’d rather not proceed building the buffer amplifier until I was reasonably sure the oscillator was working. Any ideas, oh wisdom of the internet?

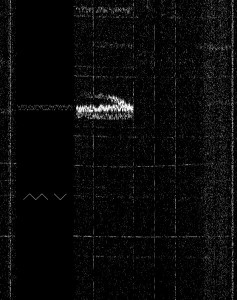

Addendum: On a whim, I swapped out a color burst crystal (3.579Mhz) and it started to oscillate. As i tough various components, I get a stronger signal, but relatively little frequency shift.

I’m hypothesizing that my substitution of the 220pf for the 390pf ones wasn’t entirely kosher.

Addendum: Here’s some video:

Addendum2: Heh. I think the transistor was in backwards. Reversing it, and it now oscillates on 40m. Thanks to Eldon Brown for the suggestion, which made me double check. Next stop: a buffer amplifier!

Addendum3: It oscillates at 7.038616 Mhz or so.