Tonight was a total lunar eclipse…

Lunar eclipses are pretty, but not super rare. Tonight’s started before moonrise, and by the time I got out to snap a picture or two, totality was already over. More interesting perhaps than the eclipse was the optical gadget that I pulled out to have a look.

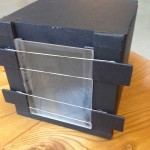

Over the years, I’ve acquired a bunch of optical gadgets at auctions and garage sales, and through my hobby of building telescopes. One of my best acquisitions were a pair of tripod mounted binoculars. I haven’t had them out in a few years, but the eclipse gave me an excuse.

These are German WWII aircraft spotting binoculars, probably manufactured after 1942. I got them at an auction of optical gadgets from the estate of a Chabot Telescope Makers Club (whose name is shamefully escaping me at the moment). I do remember that Kevin Medlock was the auctioneer, and made sure that I didn’t get them too cheaply. I believe that he had a pair that he restored, and if memory serves, he replaced the eyepieces with better Erfle eyepieces (which he machined to fit in the original barrels) and had the objectives sputter coated.

Mine aren’t so cool, but they are in pretty good shape.

I know I looked up some details on them when I acquired them, but I am not certain I wrote anything down, so tonight I dug around trying to find more information about them.

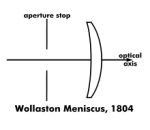

Looking at the markings is helpful. 10×80 is the specification of the binoculars, just like modern binoculars. 10×80 indicates that the objectives are 80mm, and they magnify 10x. D.F. stands for Doppelfernrohr (double telescope). The initials above the serial number are “dkl”, which indicates that they were made by Josef Schneider, Kreuznach. Binoculars of this type were manufactured by a number of different companies, all comparable in terms of their performance and quality.

Here’s an article on restoring them.. He includes some great information about the type:

In 1936, Emil Busch AG of Rathenow won a contract to produce a 10x binocular for air observation for the German military. Leitz and Möller each produced competing prototypes, but the Busch model was chosen for its lighter weight (6.5 kg vs. 9.25kg for the Möller and 8.5kg for the Leitz) and greater field of view (131m at 1000m vs. 105m/113m for the Möller/Leitz models). Production began soon afterwards and continued through the war, when the Busch design was also produced by other firms in Germany and occupied Poland. The markings of the different factories are listed in the following section. All models have identical optical systems: 80mm cemented achromatic objectives with 280mm focal length, 70-deg eyepieces, 45-deg Schmidt roof prisms. Due to allied bombing, the 10x80s were primarily used for identifying attacking aircraft and directing the large 4m rangefinders, searchlights and cannons of the anti-aircraft batteries around German cities. They also proved useful on the battlefield, and a version with 20-deg inclined eyepieces was produced for use at sea. A single half of the 10×80 binocular served as Z.F. (Zielfernrohr) 10×80, a sight for the 8.8cm artillery.

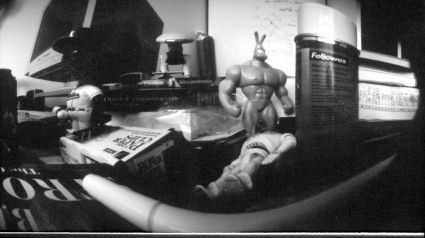

Mine are missing a few parts: there is some sort of mounting block which is over the top, and mine is missing the filter wheel that is toggled from a (missing in my pair) knob to the left of the viewer. I’ve put a piece of Scotch tape over the empty hole to keep dust from getting inside. Mine are also missing

Thousands of these were made, and a lot of them are still kicking around. They are pretty awesome for doing astronomy. The tripod I have is made from a solid hardwood (oak, I suspect) and is super strong and stable. A lot of the ones I see on eBay and the like have been stripped of their original finish, and often are buffed to a comically shiny bare metal look. Yuck. I suppose since many are recovered from damaged condition, not much is loss, but mine are in pretty good shape, so I think I’ll try to keep them as original as I can.

Tonight’s picture was captured by just holding my iPhone to one of the eyepieces. The view through the eyepieces is quite a bit nicer, the low light makes the autofocus not function well, and you can see there is a lot of noise in the sensor.

Over the next few days, I might do a similar post about my microscope. Stay tuned.

Addendum: After totality had completely ended, I went out and took this shot. It was difficult to get the iPhone to set the exposure correctly, and I used the digital zoom feature to get it large. The result has a pretty good view of the larger features, but is kind of mushy and looks like it was painted, rather than photographed. Still, you can see the system of rays emanating from the crater Tycho. I wonder if there are camera applications for the iPhone that allow better adjustment of parameters. I may try again sometime soon.

A picture after totality, I think it's still in the penumbra. pic.twitter.com/ySqCx2NoxR

— Mark VandeWettering (@brainwagon) September 28, 2015